(Note: all bibliographic information, including the works cited page, has been removed from this essay)

In 1817, three hundred years after the posting of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, students held a book burning at a castle in Wartburg, Germany, where Luther had stayed after being excommunicated. Student associations had organized this ceremony to burn “anti-national and reactionary texts and literature which [they] viewed as ‘Un-German.’”

Such student-led censorship occurred again in Germany on May 10th, 1933, when students played a fundamental role in another movement to destroy literature and culture deemed “un-German.” In the months leading up to May 10th, Nazis would terrorize authors in many ways; they called them on the phone repeatedly and vandalized their homes, with Jewish writers persecuted even more intensely, often being “publicly mocked.” The attempt to assimilate Nazi principles into German ethics and culture had begun. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, headed a movement promoting the integration of Nazi ideology specifically within “German arts and culture.” This included the eradication of any form of culture which the Nazis deemed “degenerate.” This time of censorship quickly led into an era where “freedom to gather, freedom of the press, and freedom of expression were all restricted.” This restriction was done unofficially, without the use of governmental authority and enforcement; instead, it was led by students and influential members of communities. Historian Leonidas Hill explains that the students met with tacit approval from authorities as the “Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda welcomed the student initiative without contributing to the preparations.”

Student associations in particular began to encourage the censorship movement on April 6, 1933, a month before the burnings, when the Nazi German Student Association’s Main office for Press and Propaganda proposed “Action against the Un-German Spirit.” This officially announced student support for destruction of literature. Two days later, on April 8th, a preliminary document of “twelve theses” was created by a student association. The theses “attacked ‘Jewish intellectualism,’ asserted the need to ‘purify’ the German language and literature, and demanded that universities be centers of German nationalism.” This document was published on April 12th, preceding the book burnings that would occur in the next month.

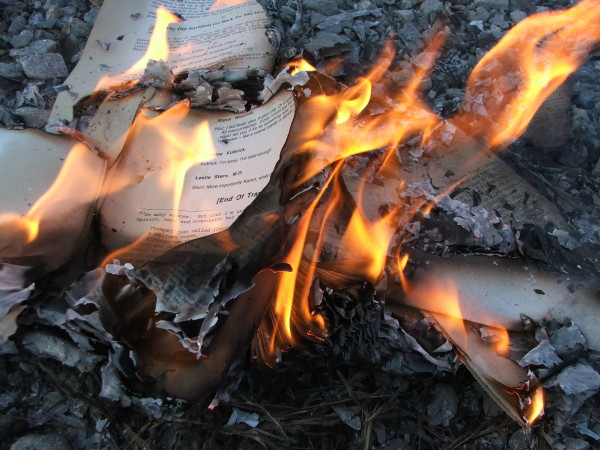

On May 10th, 1933, more than 25,000 books went up in flames when students organized gatherings to destroy what they deemed to be blemishes on German culture. A change occurred within communities; author Fernando Báez writes, “A kind of fervor . . . took control of students and intellectuals.” Students “marched in torchlight parades” through streets in organized masses to announce that they were “against the un-German spirit.” Approval of a “blacklist” of books was unofficial, but when it was publicized, government ministries supported the initiative the students had undertaken. The burnings were held “with great ceremony” and crowds gathered to watch and support. Though students led these gatherings, there were often appearances by Nazi officers and university faculty or administration. The students brought together many books written by the best authors of the early twentieth-century and “mercilessly burned” them. Erich Kastner, an author who witnessed this and had already been censored, wrote, “I stood in front of the university, wedged between students in SA uniforms, in the prime of their lives, and saw our books flying into the quivering flames. . . . It was disgusting.” The attempt to destroy all “un-German” literature resulted in copies of works by various influential authors being destroyed, including Bertolt Brecht, Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, Heinrich Heine, Franz Werfel, and Karl Marx. Historian Marc Lüpke notes that in addition to authors, other intellects bent to the actions of the Nazis and students: “Library employees and many professors went along with the emptying of their collections, even if they didn’t all agree with it.” And the pressure from government and a dedicated element of society–specifically students–pushed the movement forward. Authors who were no longer allowed to be published within German borders were also pressured to emigrate. As a result, May of 1933 was the start of a “mass exodus” of authors and thinkers.

As student associations became the leaders in the movement to destroy “un-German” culture, members of German society did not take the burnings seriously; they disregarded these events as a “student lark” even though the students had begun to organize themselves and plan attacks before May 10th, the actual burning date. In Berlin, on May 6th, students arrived at the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, a private sexology research institute, and spent three hours ransacking the building. They vandalized the furniture, carpeting, wall decorations, and simply destroyed anything and everything they found. “They confiscated books, periodicals, photographs, anatomical models, a famous wall tapestry, and a bust of Hirschfeld,” all of which were burned in the fires. Historian Leonidas Hill writes about this event and the lack of reaction, noting, “There was virtually no resistance to any of those actions from the university authorities and faculties, the students, the libraries, or the bookstores of publishers.” Competition between student associations and university organizations played a major part in the student leadership that took place. For example, the event at the sexology research institution was planned and executed by Deutsche Studentenschaft, a Nazi student organization, which aimed to “upstage” another Nazi student organization, the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Studentenbund.

The enforcement of these “unofficial blacklists” of literature and authors by burning books caught the attention of not only Germany, but the rest of the world. Because of the spread of the news, many well-known figures commented on this censorship of literature and ideology. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, gave speeches targeted towards the general public, specifically students, promoting the destruction of literature; he had stood up at one of the gatherings and encouraged the students to continue their work. Not many members of society had known about the burnings, apart from the students, and Goebbels announced that book burnings had occurred in various German cities on that date and all were product of student initiative. Goebbels was an integral supporter of this movement but he was not the only one who voiced his opinion. On the opposing side, Helen Keller, also an influential figure who spoke out directly to the students, disapproved of their actions and wrote a public letter to them in an attempt to stop the burning of books before it began. On May 9th, 1933, she published an “Open Letter to German Students,” writing, “You may burn my books and the books of the best minds in Europe, but the ideas those books contain have passed through millions of channels and will go on.”

The burning of books on May 10th, 1933, foreshadowed the events that followed in Nazi Germany. Author Fernando Báez refers to the incident as the “Bibliocaust” and writes:

The Holocaust describes the systematic annihilation of millions of Jews by the Nazis during World War II. But that event was preceded by the Bibliocaust, in which millions of books were destroyed by Hitler’s party. The destruction of books in 1933 was the prologue to the slaughter that followed. The bonfires of books inspired the crematory ovens.

Báez suggests a correlation between censorship of literature and infringement of human rights generally, and he is not the only one. As German poet Heinrich Heine wrote in 1823, “There where one burns books, one in the end burns men.”