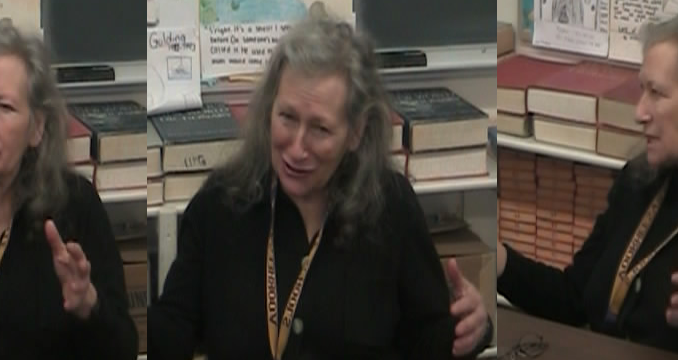

Mrs. April Levy, an English and Spanish teacher at Voorheesville High School, is one of the most interesting and insightful people I have ever had the pleasure of meeting. Anyone who has taken one of her classes knows that you learn not only about English or Spanish, but about life in general. Classroom conversations can range from modern politics to wild stories from her childhood. Even if you haven’t had the honor of being her student, you have probably heard of her renowned use of red pens–especially during research paper season! Indeed, one of the most valuable aspects of taking a class taught by Mrs. Levy is her extensive and thorough knowledge of language coupled with a love for teaching. With this in mind, I knew immediately who to go to when I was given the opportunity to interview a writer for The Blackbird Review. I am very pleased to share with you a witty and in-depth account of the life of April Levy.

BBR: We know that you’ve published Writing College English and Real Kids Don’t Say Please. One of them is obviously a college textbook, but could you tell us a little bit about the other one?

AL: It was a humor book and I got the idea when we were riding to New York–my husband and I with Morris, my oldest, son, who was a baby at the time, nine months old in the backseat–and somebody was talking about his new book, Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche. Later, there was another one that came out, Real Women Don’t Pump Gas, but I said, “Oh! it’s like ‘Real Babies Don’t . . .,’” and I don’t even remember what I said after, but I came up with a few jokes about “real babies.” And then, Dan, my husband, said there was too little about “real babies”; “real kids” would be better. I came up with “Real Kids Don’t Say Please,” and then I went with that idea. I thought it was funny, a good humor book. Actually, one of our best friends, Marco–not Rubio!–David Marcowitz, read it and said, “It’s really good. It’s not funny, but it’s really good!”

BBR: When you were in high school, would you have expected to be where you are today, as a writer and a teacher?

AL: No. Even when I was in college and graduate school, I wouldn’t have expected myself to be in a high school. I used to think that I wanted to teach, but I liked the idea of teaching nursery school or college. I didn’t really want to have anything to do with anybody in between and I initially–I actually applied to Bank Street School of Education and got in to teach early childhood education. I love little kids. One of my writing teachers said, “Why would you want to go there?!” And I did begin to wonder whether it was really the right place for me. And eventually, when I was ready to go on, when I had graduated from my undergraduate program, I had to choose between going on to a program in English or going to Bank Street, and I chose to go on in English. I really love doing research on English topics. I love medieval literature, Renaissance literature, particularly. And when I had done that for a while, I really did consider college teaching–I did some college teaching and I enjoyed it. But, it’s hard, being a college teacher; you have to publish all the time–much more than teaching. And I had begun to find that the thing I really loved wasn’t the research, but the teaching. I loved working with students. I took some Spanish courses–I knew how to speak Spanish by that time–because I knew it’d be easier to get jobs teaching Spanish than teaching English, an oversubscribed field. At the Hebrew Academy, I started teaching Spanish, then taught English as well. And when I came here, I was hired as a Spanish teacher. But I said at the interview, “If there are any English course you need taught, I’d like to do that, too.”

I love teaching high school. I think I like it a lot better than I liked teaching college just because you get to know the students better and–much to my surprise, because when I was in high school, I didn’t like a whole lot of high school students–I really love most of my students here. So that’s why. I’m delighted to be doing what I’m doing.

BBR: Is there advice you would give to your younger self or anything you would change if you could go back?

AL: Oh, God. Let’s not even go there. Yes, there are many things–specific places I wouldn’t have gone to, both literal and figurative. You know, I still have a lot writing that I didn’t pursue publication for. I used to write children’s books. At first it was just for myself, but at a certain point, I really did think I’d like to publish these things. It came down to this one day: I had sent my stuff to an agent and she was very interested in my work and she wanted to meet me in New York City. But I’m a mom with three kids. So do I regret not having met her? Well, maybe a little tiny bit. But, at the time, I was a mom and that was really what I wanted to do. I’m not really regretful, but it was a missed opportunity, I think. There were probably other missed opportunities along the way. I had an opportunity to teach regularly at SUNY, but it again meant that I would have to be at SUNY when my kids were coming home from school and I really didn’t want to do that. I took a lot of years off to be a mom. High school teaching is great because you’re pretty much out when your kids are out. And even if you have to work at home, you’re there with your kids. You can answer questions and talk to them and stuff. So that was really important to me.

BBR: You have been talking a lot about teaching. Did you ever make the conscious decision to be a writer? Did that go along with the teaching?

AL: I actually probably thought that I might be a writer. Of course you can be a writer and be many other things–a waiter or an insurance salesman. I mean, famous writers have had jobs like that. I was a writing major as an undergraduate in college and I did submit some stuff to journals. I received some good feedback and people were interested, but I was not good on the follow-through. I probably missed some opportunities that way, but I have to say, from the moment I first taught, I just realized I loved teaching. And I still do. I get a great kick out of it. I think it’s very meaningful and I don’t think I would’ve been happier not having done that and having tried my hand more ardently at being a writer. I think I’m doing what really makes me happy.

BBR: Do you still write today?

AL: Not a lot. Well, comments on students’ papers. That’s a lot of writing. But, no, I don’t. And sometimes I think about it. I’m very careful in crafting emails. I really am. I still love writing. I sometimes wonder–because I’m getting old and getting to the point where it won’t be that many years that I will be able to keep teaching. I do wonder: will I retire and start to write a lot again? I used to write a lot. And every now and then I take out my folder of old material and I think about it, but I haven’t had the energy to do it yet. So we’ll see what happens after I retire. I hope there’s a lot of years left.

BBR: Do you have any general tips on what to do and what not to do when it comes to writing?

AL: I still remember–seventh grade–a story that I wrote. We were supposed to write a little play with dialogue. I wrote a story that I called “Susan Damon and Wanda Pythias,” or something. I don’t know if you know the story of Damon and Pythias, where one substitutes for the other so that he can go home and say goodbye to his family and he’s in danger of being killed, but his friend comes back. Anyway, that story that I wrote featured a boa constrictor and it was a little far fetched. My teacher wrote on it that it’s better to write about stuff that you really know. I took it home and I was devastated because I was the poet laureate of the sixth grade. I was this wonderful gifted writer. And my mother talked to me about it. We talked and she said, “He’s right. You know, it really is better.” So I wrote another dialogue that was my mother and me talking. It was just the same conversation that we’d had. And I handed that in, I got a good grade, and I think I learned a lesson; that writing about what you know is much better than writing about something far fetched. I mean, you could write about fantasy stuff, but if there’s not some germ of it that is from your own life, from your own experience–that’s what makes Tolkien so great–except for the elf language. I mean, Tolkien writes about fantastic creatures, but they are perfectly recognizable for their human feelings and human actions. And I think that is what makes some writers just better than others. They are writing about something that is very real, because they’re really in touch with their own emotions, with their own experience, because they’re writing out of their experience.

BBR: What is the hardest thing about writing for you?

AL: Sitting down to do it. It’s a very lonely enterprise. I remember a professor talking to me about–talking to the class, actually,–in graduate school about another kind of writing: research writing, scholarly writing, critical writing, which I did a lot of in graduate school. And he talked about this one very prominent critic–a writer of that kind of stuff, critical literature–who had a technique. He would go to the carrel in the library and he would line up candy bars and he had to write so many pages before he could have the first candy bar and he’d go through the candy bars, and so managed to do the writing that he had to do during the day. I think that’s the hardest thing–just sitting down to the task. The ideas are often there, but it’s very hard and you are pulling something out of yourself. You’re not really, at the moment, communicating with anyone. I’m a real revisor, so I will read over everything and carefully revise again and again. It’s just hard to pull yourself away from real life to do that, but it’s really necessary to do. I’m looking forward to that. I might do that again.

BBR: Who is your favorite author?

AL: My favorite poet is Robert Browning. I memorized a seven-page poem by Robert Browning just because I’d read it so often. I sometimes need a little correction, but at the time I didn’t even mean to memorize it. I just read it so many times to myself, aloud mostly, that one day I realized I didn’t even need to look at the pages. I just had it. Obviously, Shakespeare is fabulous. I took a lot of coursework in Shakespeare. I love Chaucer. I can’t share it with that many people because of the Middle English, but I love Chaucer. Of modern writers, I love Twain. I think Huckleberry Finn is the great American novel. I just saw the film version yesterday again of Billy Budd. Billy Budd is a great story. Melville is a great writer. And I love the books I teach. I love Dickens. I love Emily Brontё. Jane Austen is pretty good, too. There are a lot of good writers out there.

BBR: What is your favorite thing about writing?

AL: I think it’s words that so appeal to me–having the precise word for something, capturing in precise words exactly what I want to say. Even when I write emails–I’m not kidding–I’ll go over them, I’ll change the words, I’ll look up words to make sure I’m using exactly the word that I want to use. I’m talking about emails to my kids! I do this regularly. Finding just the right words to articulate something is something that is very meaningful to me and always was. I love words.

BBR: What is your favorite thing about teaching English?

AL: There are a lot of things. I don’t think I have one favorite. It’s a great pleasure and a thrill to be able to teach texts that you think are great and to look at them again and read them again and realize again and share with others what’s so great about them. We looked at an AP Exam text today, in AP English–a little excerpt from the novel McTeague. And it’s so well written–every detail. The kids hadn’t understood it. Most of the kids had thought one thing about the text–the opposite–missed the irony. I love irony. And it’s just wonderful to look at a piece of writing and see how beautifully crafted it is. I mean, it’s like looking at any piece of art or piece of furniture or a beautiful meal that’s just perfectly crafted and you appreciate every little detail of it. That’s what I love about it.

BBR: What do you think makes a story good? Are there any specific qualities, besides incorporating your own experience?

AL: Well, I think that last word, detail . . . We’re just reading Fahrenheit 451 again. There’s that little place–it’s not a great novel, but there’s that one part in Fahrenheit 451 where Bradbury has Faber talking about the detail that used to go into older things that’s no longer a part of what he sees around himself. We’re going back to the 1950’s, but in television and in movies, he is feeling like all of that is not as good as it used to be. It doesn’t have all of the texture, all of the details. I don’t think it’s true that it has disappeared from things, that it’s not part of living in the world. But that is what I appreciate in almost anything. You look at a painting that you really love and, yes, the whole painting affects you, but you look at one thing and another little piece of it and you appreciate something that the artist is saying through that painting. And it’s the same with literature. So detail is very important. That’s why I test you guys so cruelly on the texts that we read because it is by the detail that you understand what’s happening in a text. And it’s through the detail that the writer makes you his puppet, makes you feel what he wants you to feel, makes you experience what he has experienced or wanted you to.

BBR: What advice would you give to aspiring writers?

AL: I guess just to keep at it. I say that with some reservation, because there are times when you realize something else is actually more important to you, that you’re better at it, that it’s more important to you or the world. As I said, writing is not easy. It’s hard. But I do think that anything that you do well takes real effort and so if you’re a writer, I believe you can’t do it casually. You have to really commit to it. Commit time. Commit effort. Commit thought. Commit energy. Commit to the awful feeling of having stuff marked up and rejected or just read it again and say, “What the heck did I–? Why did I write this?” and knowing you have to take it apart again. Be willing to experience those very hard moments and go on. And that’s not just for writers–that’s for pretty much anything that you want to do well. Persistence like that is necessary. Tell that to Marco Rubio. That might help.