Dakota didn’t want to give her grandma a reason for her sudden onset of nausea. She told her she was going to puke, and that perked her right up. She ushered her off of the couch and into the bathroom where Dakota knelt to the toilet. Her grandma held the wisps of her braided hair back, waiting until Dakota’s body convulsed. The seconds ticked away on the clock above her. She vomited.

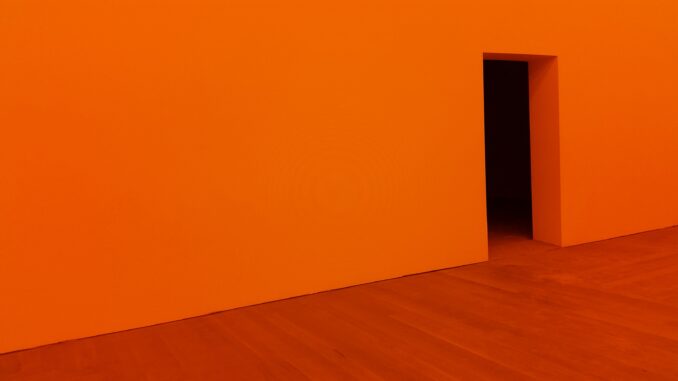

Her grandma had not asked why she felt sick. She was too busy rubbing Dakota’s back and whispering something Dakota tuned out. She knew why. It was that glaring orange color that flipped her stomach on its side. Disgusting, putrid, loathsome orange.

With Dakota’s head now pathetically draped across the toilet’s rim, her grandma reached over and flushed it. She shuddered and grabbed her Febreeze like it was a rosary, spraying like a maniac. It got in Dakota’s eyes, and she blinked rapidly, breathing hard, lungs clenched tight. Remnants of the puke bit at her tongue.

Her eyes lazily trailed back to the clock. It looked like a paintable from a craft store. It was a very funny looking giraffe. Her grandma hadn’t seemed like the whimsical type though. So who could have…An image of her dad burrowed into her head. She could see his little hands with a big paintbrush trying to make it look perfect. She could see him showing his mom and the proud expression on her face when he placed it on the toilet tank to stay there and tick and tick and tick.

Her grandma’s voice broke her out of her trance, “I’ll be right back, I’m going to grab you some mouthwash.” Her hand touched Dakota’s shoulder. Dakota twitched, eyes anywhere but the clock. She would not think about him.

Her limbs felt like mushy pulp. What was the point of even getting up? She felt like crap. Who was she to make her grandma hold her hair back? To give her mouthwash? This must have been too much for her grandma to handle; she took in her son’s kid at the last minute.

What if she didn’t want her? Her heart panged in her chest at that thought. No, she concluded, she was just being stupid. Her grandma wouldn’t have taken her in if she didn’t want her.

Her heart still thrummed.

Dread bubbled from the pits of her stomach, slithering up to her mouth, dripping down her chin and making its departure into the toilet. The bile made her eyes water.

Her grandma stepped back into the room. “I’ve got different types. Your grandpa always gets those two for one deals at the store and well…” she set the bottles down on the sink with a soft tap. Dakota lay still until her grandma sighed and walked away.

She waited and waited and nothing happened. Nothingness filled her with an empty relief. Her mind was blank. It was at this point that she hoisted herself back up off of the floor, and looked at herself in the mirror. There was a bright red line from the toilet bowl’s rim imprinted on her cheek. She touched it with her fingers. It was numb. How long had she been on the floor? Minutes? Hours? She dry swallowed and remembered what she had to do. Picking up one of the bottles, Dakota swished the liquid around in her mouth for far longer than she needed to and spit. The blue liquid went down the drain and there it was again. The incessant ticking. A needle going further and further in. She balled her hands into fists and reached down to where the power outlet was and ripped the wire out.

Silence.

When Dakota resurfaced back into herself, she stood in the kitchen. The cold still stuck to her like wet tissue. Her grandma was across the room, making French toast. She dipped the bread into the eggs, putting them on the skillet. She sighed when she heard them sizzle.

The smell pricked her nose; it smelled like home. She nibbled on the inside of her cheek, trying not to cry or vomit. She would not go back into that flowery scented puke bathroom. She sat down in the nearest chair and closed her eyes, trying to calm herself. She swallowed it down, down, down, until it hit the pit of her stomach.

Her dad hadn’t been much of a cook but he could make great French toast. When she was seven, homemade dinners had just become a thing. Her dad got a promotion at the sales agency he was working at, and life became embedded with sickly sweet syrup and bacon and French toast. She never got sick of eating it, though. Life was good. Better than good. She smiled ear to ear every day and so would he. He had that smile that made you feel okay. It was warm. Homey.

But then she was twelve and they went back to microwaved hamburgers. She hated those things. They were soggy yet dry and they made her even hungrier. But not one complaint passed her lips. She didn’t know why French toast dinners stopped or why her dad only bought one microwavable hamburger and excused himself from dinner. Never hungry. Always too tired, as he would put it. But they could still spend some time together while she ate, so maybe it was okay.

Then she turned thirteen and realized it wasn’t. At first, he started to skip family dinners once a week. He flitted around the house, and wouldn’t look at her, barely talked to her; he was ghost-like. But it was okay. On the bright side, now she would only eat those disgusting hamburgers six times out of the week. Plus Dakota’s friend would let her have some of her lunch after Dakota would ask her for some. It became their routine. Dakota gets one half of the sandwich and her friend got the other. It worked.

Then he skipped every other day.

Then he stopped coming to the house.

She called the police. They came. She opened the door with shaking hands. They took her to the station, sat her down in a cold chair and gave her a small cup of water. She didn’t touch it. They asked her questions. She answered. Social services were called and showed up hours later. They took her by the nape of her neck and plopped her down in her grandma’s house like a rag doll. Her new happy home.

It was the start of her second week there. When the weather turned disgustingly warm and soupy and the sun singed the edges of the sky. The police showed up at her grandma’s door and told them her father had died. An apparent suicide. They left as quickly as they came. After the door shut with a harsh click, her grandma glared through the glass and spat. The spit dribbled down. It was slow.

Soon after, Dakota sat upright on her grandma’s couch.

She was being stupid. She knew that.

It didn’t stop the thoughts from climbing one on top of the other, though. The thoughts of her dad still alive. Smiling. Talking.

Her grandma trudged into the room. In her hands, she held onto a black binder with a sticky note on it, reading, Tommy and family. Dakota shifted as her grandma sat down on the same couch.

“There are some photos of your father here.” Her grandma smiled down at the binder. “Some of them might be blurry. Your grandpa was always the better photographer.” She set it down on the couch space between them.

They’re just photos, they don’t mean anything, Dakota thought. She picked it up with stiff hands. She opened it. And there was her dad. There he was eating a hamburger, the mustard dribbling down his chin. There he was with a toothless grin giving a big thumbs up. There he was moving into his college dorm, spread out on his bed like a starfish, laughing. There he was holding Dakota’s red and tear-stained face when she was born.

Then there he was standing beside her and her grandma. She looked closer, questioning when this had been taken. She turned it over. No date. She studied the photo again. Then her eyes fixed on it. Dad’s orange tie. His lucky tie. He wore it to work every day after the promotion. Dakota’s skin grew pale and hot. She knew she was going to puke.

Her grandma set the plate of French toast down with a clatter. Billows of steam rose from it like a comforting hand beckoning them to eat it. She must have made enough for six people. She put down another plate with the disfigured and lumpy omelet. They sat across from each other, each with an empty plate and untouched silverware. Neither reached for the food.

“Aren’t you hungry?” there was a tick in her grandma’s voice. The cry of desperation.

Dakota shrugged, making herself smaller in the chair.

Her grandma’s face curved and shifted into a shaky frown. “I got off the phone with your grandfather while you were in the bathroom.” She waited for a beat. “I told him what happened,” she searched Dakota’s face after she said that. “Dakota, I’m not going to tell you the right way to grieve because even I don’t know.” She searched for the right words. “It’s terrifying. No one tells you that,” she breathed in harshly, “but I want…I want to tell you that it’s okay to be sad or angry or anything and everything. You’re you. You’re dealing with this and so am I and so is your grandpa. We’re here.”

Dakota had tried to be strong. But the efforts of chewing on her lip, drinking her glass of water empty, and bobbing her leg up and down didn’t work. Her face was tearstained, her grandma’s as well. Her grandma stood up from her seat and walked over to the fridge taking out a bottle of syrup. “I’m going to eat,” she sniffled, “and so are you. Okay?”

Dakota nodded, wiping her warm face with her sweater sleeve. Her grandma sat back down, opening the syrup and drizzling some on the French toast. She looked up, blinking rapidly before cutting the food into tiny bits.

Dakota swallowed and cleared her throat. “Can you…” this was hard. “Can you pass the syrup?”

Her grandma smiled warmly. She nodded, passing it to her. They ate peacefully.